Review by Kiritori Mederu | Technology, historical awareness, and human individuals

Historical awareness inspired through displays and movies

In a dimmed room on the second floor of the Tokyo Photographic Art (TOP) Museum, seven vertical displays suspended from the ceiling with wires, are quietly emitting light. The screens are filled with enlarged low-saturation images that slowly move from right to left. The sense of tension this movement creates, evokes the examination process of scanning photographs for dust or other unwanted objects. Hosokura Mayumi’s “digitalis” series presents a contemporary take on post-production in photography. The photographs here move at a speed that allows them to retain the illusion that they contain images, and the images they do contain are at no point reduced to mere light.

In the next room, several displays are put up in a vertical direction, flickering continuously without converging into concrete images. There are displays with missing dots, while on others the color filters are broken, or the backlight is exposed. The displays are pierced by metal pipes, and I wonder how they are made to emit light… The flickering displays don’t let me recognize any shapes of light, let alone concrete images, so what I look at here are nothing more than displays in their contemporary function as support media for all kinds of information. This is Death by Proxy #3 by Houxo Que.

HOSOKURA Mayumi, from the series “digitalis,” 2021 Photo: INOUE Sayuki

Houxo Que, Death by Proxy #3, 2020, Mixed-media installation, Dimensions variable Photo: INOUE Sayuki

The theme of the Yebisu International Festival for Art & Alternative Visions 2023 is “Technology?” with a question mark that suggests the underlying question, what exactly we mean when we talk about “technology” in this day and age. Some may think of AI, software like ChatGPT that answers emails for you, paints, or even calculates the opening lines for your novel in a matter of minutes. At this exhibition, visitors are repeatedly confronted with this term that is usually associated with “innovation,” and that here works as a trigger that inspires them to review what “technology” is in the first place. The curatorial idea behind connecting the above-mentioned works by Hosokura Mayumi and Houxo Que, for example, was to exhibit the technical requirements that have come to dominate the present-day society: how an “image” is defined by the light of the display, and how high its resolution is.

Shown on the same floor are: a piece by Koshida Noriko that continues to surprise, showing a simple set of tables and chairs filmed from multiple angles, and subsequently edited and choreographed in complex ways; footage of a performance in which Trisha Brown utilizes harnesses and ropes to create a world in which physical movement is disconnected from gravity, and thus shakes up empirical rule; and the latest work in Lu Yang’s “DOKU” series, in which a 3D model with the artist’s face – reproduced down to the last pore by way of photogrammetry – dances through a world centered around elements from fighting games and the six posthumous worlds (hell and heaven) in Buddhism, as a show of liberation from contemporary woes.

Revolving around cosmological examinations regarding ways of understanding the world, mechanisms for regulating physical bodies in imagery, and methods of filming them, these works – each with its own aesthetic in terms of picture resolution – subtly make the viewer aware of the history and the transition of technology as a common foundation, or in other words, of his or her own point in history at large.

KOSHIDA Noriko, On the Shore of the Desk, 2010, Double-channel video installation

Collection of Tokyo Photographic Art Museum Photo: INOUE Sayuki

Trisha BROWN, Homemade, 1966, Single-channel video Photo: INOUE Sayuki

Bearing in mind the aspect of timelessness in Buddhism, compared to the Christian view of life and death, the philosopher Yuk Hui suggests that it requires technological awareness to generate the historical awareness that people in East Asia are lacking, but that one needs to be wary of a national sense of mission of sorts that may arise according to the formation of such awareness. The “cosmotechnics” that Yuk advocates, is a reconsideration of diversity (as opposed to nationalism) that examines technology, or the way each technology is rooted in the world (cosmos).

While views are divided regarding the initial invention of video and photography that this exhibition revolves around, they certainly represent one perspective that suggests that, considering the relatively short history and synchronous universal development, “technology” can be bundled together into one historical thread. What is the historical awareness then, that is built upon the subject matter of this exhibition – “technology?” For an answer, let us proceed to the displays in the basement.

The pros and cons of positioning works according to photo and video technology

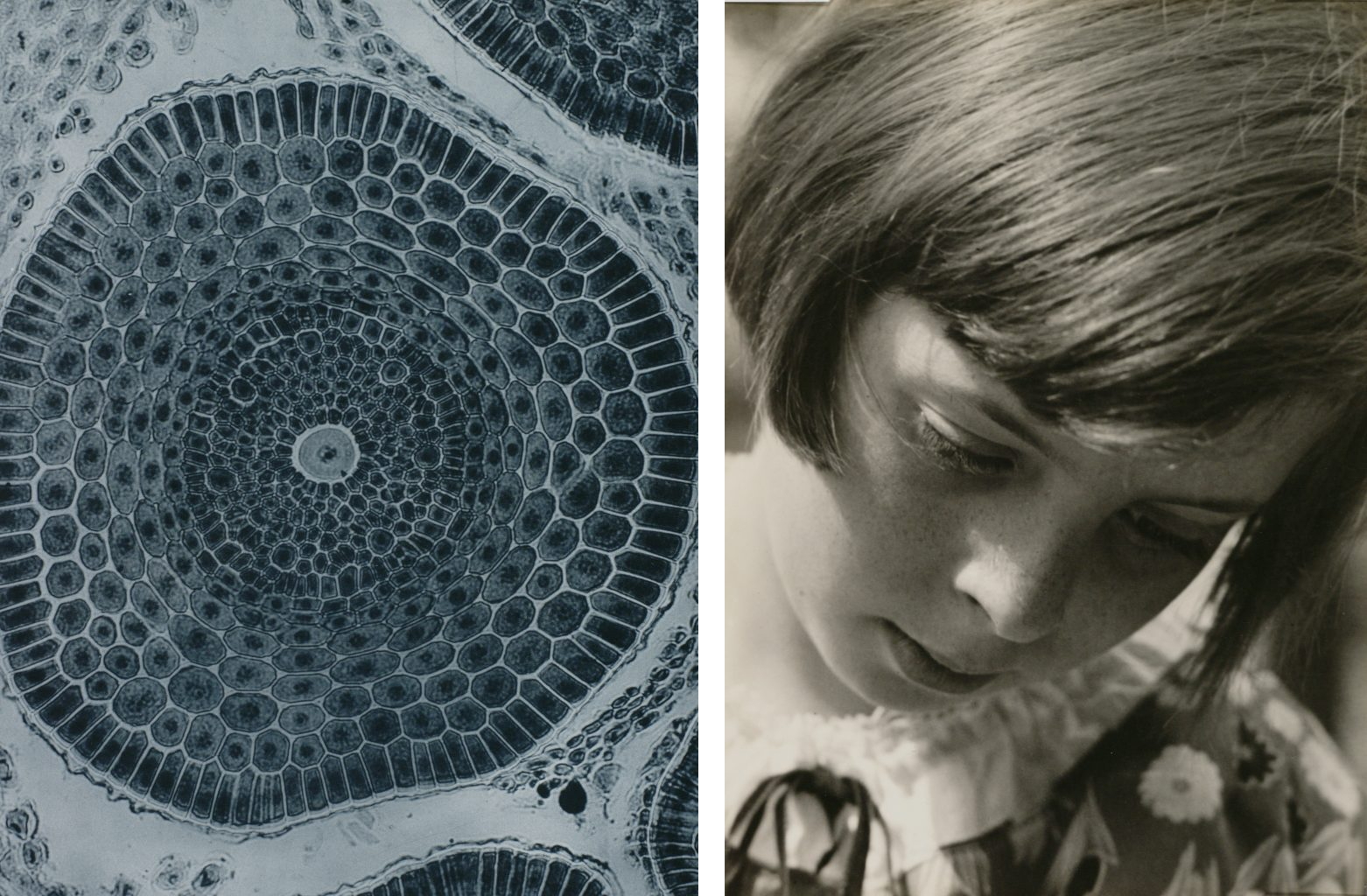

On display in the first room of the basement exhibition, are Laure Albin-Guillot’s Racine d’orge (coupe) and Aenne Biermann’s My Child. Both of them were made in 1931. The former is a microphotograph, the latter a photograph inspired by the movement of Neue Sachlichkeit that aims to capture everything in a realistic style. Thus the two works probably belong to the category of photography defined by technology. However, their meanings change completely when looking at the captions, which tell us that Albin-Guillot dedicated her work to her late husband, a former specialist in microscopic specimen, while Biermann took this photograph two years before she died and left said child behind.

Both works suggest that, thanks to the cold and impersonal gaze on the subject – an aspect introduced by the invention of the camera – it may be possible to reproduce the gaze of the absent husband, and the gaze that Biermann was supposed to cast at her children. Here, the framework of photo technology, which is usually associated with the cold, mechanical eye of the camera, is gently infiltrated by the human factor of the creators’ private affairs.

Left: Laure ALBIN-GUILLOT, Racine d’orge (coupe), from the series “MICROGRAPHIE DÉCORATIVE,” 1931 Collection of Tokyo Photographic Art Museum

Right: Aenne BIERMANN, My child, 1931 Collection of Tokyo Photographic Art Museum

This exhibition room is a whirlwind. Next is Sugiura Kunie, who photographed plants just like Albin-Guillot. Botanicus 13, 1989 is a photogram made by directly exposing flowers placed onto photographic paper, and as if to stress that it is impossible to take exactly the same picture twice, it enquires about the meaning of human intervention, and indicates that the technology of photography is not easily defined. Yamazawa Eiko’s vivid color photo Objects, on the other hand, is a picture on the abstract side. Composed of a stage and objects created by Yamazawa, it may seem like an entirely controlled photograph. Nonetheless, in color photography sans the precondition of post-production (using software), developing a photograph was a greatly impersonal operation. The question mark in “Technology?” works like a tag that timestamps Yamazawa’s seemingly timeless work.

Left: SUGIURA Kunié, Botanicus 13, 1989, from the series “Botanicus, ” 1989 Collection of Tokyo Photographic Art Museum

Right: YAMAZAWA Eiko, Objects, from the series “What I’m doing-positions and Directions,” 1986 Collection of Tokyo Photographic Art Museum

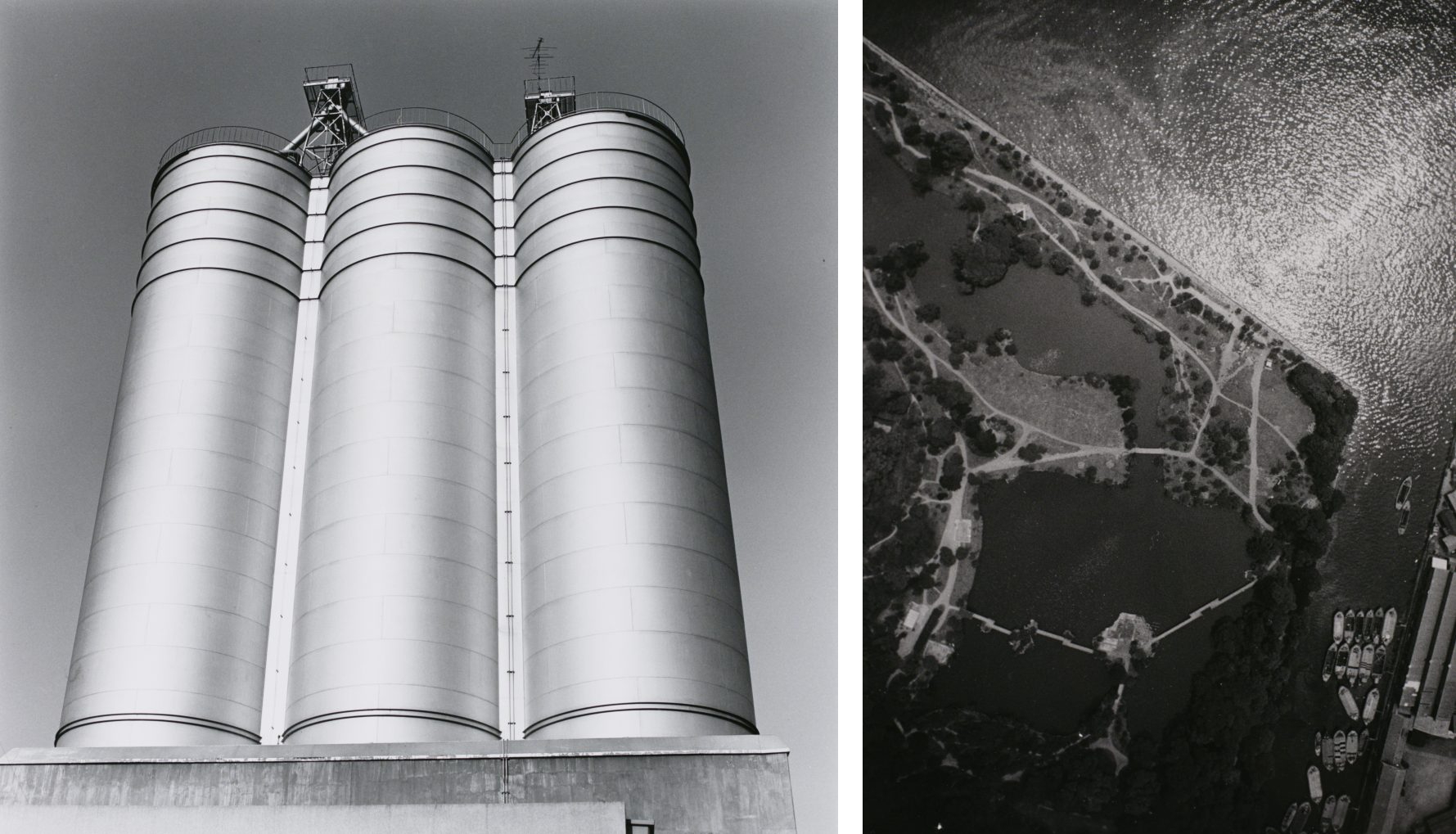

Within the context of these constructed photographs, in the landscape photos in Tsukiji Hitoshi’s “Shashinzo” series, showing parts of massive concrete buildings, thick forests, or facilitities behind grassy planes among others, it becomes particularly clear that these subjects have been deprived of their characteristic properties. Emerging instead is the photographic criterion of “how an image is constructed through reflections of light.”

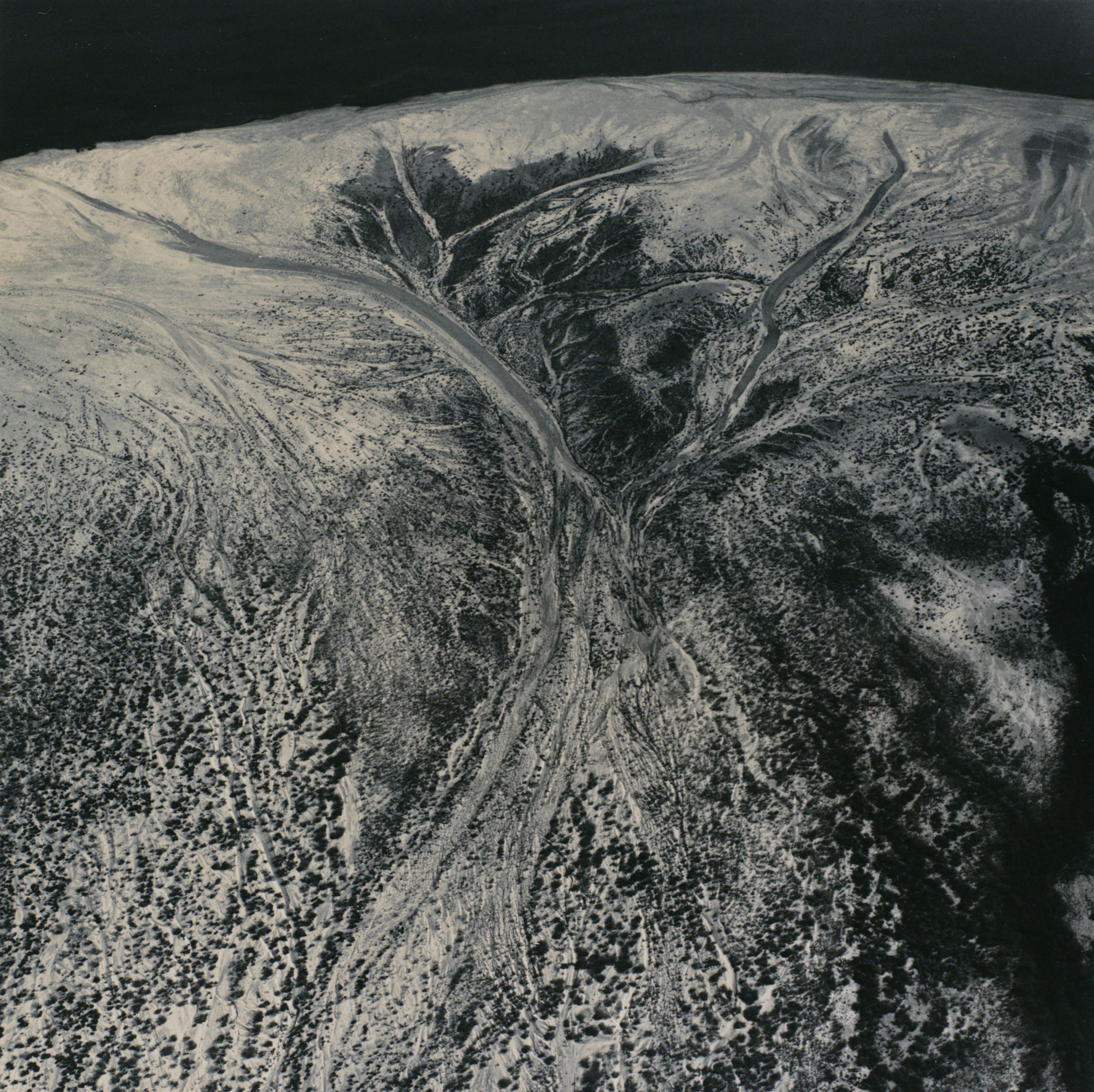

Kitadai Shozo’s Hama-rikyu Gardens, a landscape photo just like Tsukiji’s, is a picture of Tokyo shot from a helicopter. In 1957, the year after this work was made, the Soviet Union successfully launched Sputnik, the world’s first artificial satellite, inspiring in Japan a reexamination of the relationship between art and technological innovation that had reached cosmic level. Preempting that general “leaving the earth” mood of the times, Kitadai’s works embody the momentary nature of photography even more than Tsukiji’s, in terms of how “photography” has been dealing with the aspect of technical innovativeness. Also on display is The Edge of the Salton Sea, California by Emmet Gowin, who turned towards aerial photography after a volcanic eruption in 1980. Suggesting the necessity to go up into the sky in order to capture the traces of natural disasters and human activity on the planet, the work represents another contrasting layer in the overall structure of the exhibition.

Left: TSUKIJI Hitoshi, from the series “Shashinzo,” 1984 Collection of Tokyo Photographic Art Museum

Right: KITADAI Shozo, Hama-rikyu Gardens, 1956 Collection of Tokyo Photographic Art Museum

Emmet GOWIN, The Edge of the Salton Sea, California, 1990

Collection of Tokyo Photographic Art Museum

And the layering continues. In the video installation Echoes from Clouds by Umezawa Hideki and Sato Koichi, documenting the water cycle in a city starting from a dam, the mechanic eye in the filming process mimics certain behavior. The viewpoint of the camera shifts between that of a human, a flying bird, or something impersonal. In the context of this exhibition, the work may be positioned as “imagery after the age of the mechanic eye.”

Shown in the last room of the basement exhibition, is Fiona Tan’s absurd film and video installation Lift, showing the artist as she is lifted into the air by countless balloons. This work, made in 2000, is projected onto a screen along with the rattling sounds of reels and a projector. Visualizing the relationship between imagery and the “aviation” theme, which appears at several points throughout this exhibition as a connection between technological development and a human desire as old as history, through media like the now obsolete film that evokes a past when “flying in the sky with balloons” was a fairytale-like fantasy, the work adds just another facet to the matter.

The visitor is reminded time and again that the history of video and photography cannot be solely discussed by referring to the development of related technologies.

UMEZAWA Hideki + SATO Koichi, Echoes from Clouds, 2021, Mixed-media installation Photo: INOUE Sayuki

Fiona TAN, LIFT, 2000 Collection of Tokyo Photographic Art Museum

Imagery in various domains and technologies

At the entrance to the basement exhibition space, Jikken Kobo’s Tales of an Unknown World made in 1953 using the “auto-slide” projector of Tokyo Tsushin Kogyo (today’s Sony Corporation), portrays in a caricature style how nuclear power and other technical inventions have changed the world. For Jikken Kobo, a collective pursuing a composite art form through collaborations between individual artists from the fields of music, photography, print, etc., the technical possibility to synchronize music and slide projections meant that they could easily draw from both realms to define the expressive style of each of their works.

In the lobby on the second floor, computer graphics from around the world are showcased in the systematic video archives of the “Computer Graphics Anthology” and “Computer Graphics Access 89-92,” continuously for the duration of the Festival. The works shown here demonstrate the different specialized visualization technologies that have been demanded across the fields of industry, broadcasting, art, advertising, scientific research, and others. Needless to say, a significant number of these videos are commissioned works. The Shin-riken Pictures film production, for example, was assigned to make a promotion video for the Japan Bicycle Industry Association. They eventually collaborated with Jikken Kobo on Ginrin (Silver Wheels), the first special effects color film in Japan, which hints at the potential in commissioned work to inspire new creation.

Jikken Kobo (Experimental Workshop), Automatic slides projection, 1953/1986

Private collection Photo: INOUE Sayuki

The Yebisu International Festival for Art & Alternative Visions has been gathering works that are worth seeing when discussing “imagery” in Japan today, based on research conducted at places around the world by a planning team led by an artistic director. Added to this program in 2022, was the “Commission Project” as a new platform for directly commissioning artists to create works. A jury comprising Oki Keisuke, Saito Ayako, Leonhard Bartolomeus, May Adadol Ingawanij and Tasaka Hiroko, eventually selected Kim Insook, Yu Araki, Oki Hiroyuki and Hayama Rei, from the viewpoints of “continuity, experimental quality, extensibility of media, and internationality.”

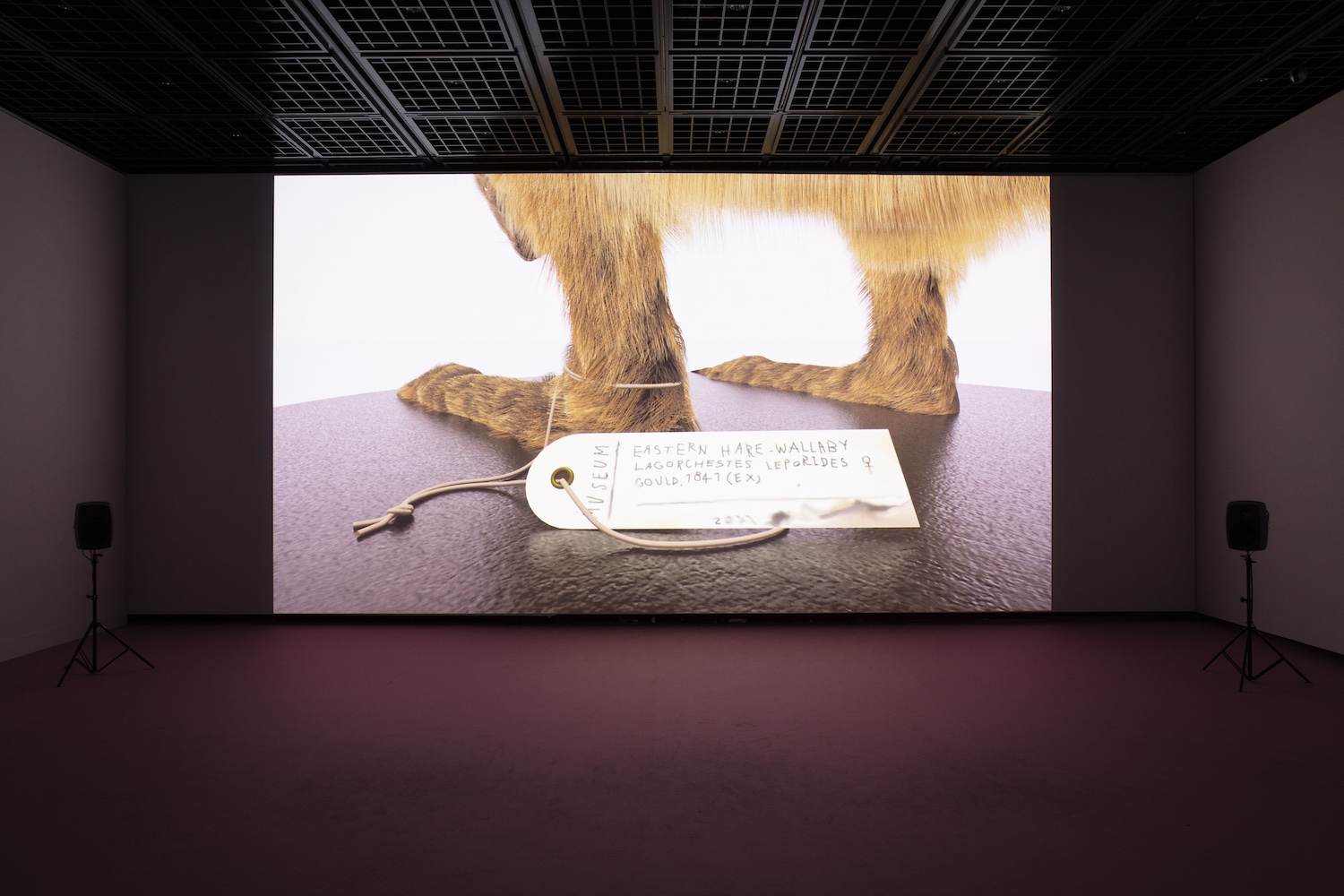

The resulting works were unveiled on the third floor. While each of these four creators mainly works with video, each of them operates within a totally different shooting range. In meta dramatic, Oki Hiroyuki sets up a spectrum of performativity within a video, and stages an actual performance (by the artist himself) behind the visitors watching that video. Through this extension of media, with a bidirectional connection between the formats of imagery and the human body, he explores what “dramatic” quality is all about. Hayama Rei’s Hollow-Hare-Wallaby is a video in which the camera seems to be gliding along the surface and the inside of a 3D computer-generated model of a taxidermy of an Eastern hare-wallaby, an extinct species of which very few eyewitness records exist. The work anticipates an age in which the world will be flooded by 3D computer graphics with digital data of things like a taxidermy of an extinct species – something that, in a double-fold meaning, only exists in our imagination – behaving like a thing in the real world. In this sense, the work can be understood as letting us take a peek into the coming age by way of imagery.

OKI Hiroyuki, meta dramatic, 2023, Single-channel video installation, Dimensions variable Photo: INOUE Sayuki

HAYAMA Rei, Hollow-Hare-Wallaby, 2023, Single-channel video Photo: INOUE Sayuki

Kim Insook’s Eye to Eye, on the other hand, is composed from Kim’s conversations on school life with children at the Colégio Sant’Ana in Shiga Prefecture; footage of the princpal’s busy day running the school; and video portraits of the children. The Brazilian people who relocated to Shiga in order to work at car factories among others, have next to no chance to mix with the Japanese society, and non-Japanese children don’t even have the opportunity to learn the Japanese language. Against this backdrop, Kim invited the children that she had spent a large amount of time with, to come and see her exhibition. The way the artist – a grand child of immigrants herself – sets up meetings at the place of her exhibition in order to tackle the massive obstacle of the language barrier, is absolutely touching. Interviews with people are the essential parts also in Yu Araki’s Unmasked (Bootleg). Araki follows the members of WISS, a Nantan, Kyoto-based covers band imitating the American hard rock band KISS, to create a detailed portrait that tells the band’s story from the beginning to the present day. The things that drive them, the meaning of living one’s own life, and the sparkle of “WISS” that, although lit through the idea that is “KISS,” is unique and original – all these things rain down ceaselessly on the visitor through interview footage and LED vision from a ceiling-high display.

KIM Insook, Eye to Eye, 2023, 10-channel video installation, Dimensions variable Photo: ARAI Takaaki

Yu ARAKI, Unmasked (Bootleg), 2023, Two-channel video installation Photo: INOUE Sayuki

At the symposium “Commission Project: Possibilities in Commissioned Work and Imagery” that was also part of the Festival’s program, external judges appreciated especially the fact that there was no age limit for participating artists, and that artists were not only commissioned to create works, but also received support in their work. From the four commissioned artists, Kim Insook and Yu Araki were subsequently chosen for special awards. The fact that two award were given is particularly noteworthy, because it was also a statement that emphasized that, “alternative visions” as pursued in the Festival, are not about ”technology” alone.

Kiritori Mederu

Born in 1989. Art critic, digital photography researcher. Her criticism focuses on 21st century formalism and media-aware artworks. In 2019, she curated the exhibition “It’s not a grave yet.” (Purple Room Gallery, Kanagawa, Japan). Since 2017, she has published the art-oriented zine Pan no Pan (meaning “meta-pan”). Co-editor of Instagram and Contemporary Image (Tokyo: BNN, 2018), comprising a Japanese translation of Lev Manovich’s essay of the same title, and nine texts by Japanese contributors.

Reference literature

-

- Mizue, No. 630, January 1958, Bijutsu Shippan-sha.

- Shedding Light on Act in Japan 1953, Shedding Light on Act in Japan 1953 Exhibition Executive Committee (ed.), Meguro Museum of Art, Tama Art University, 1996.

- Yuk Hui, The Question Concerning Technology in China, MIT Press, 2016