Dublin-born and Glasgow-based artist Duncan Campbell, winner of the latest Turner Prize for Contemporary Art, is currently showing film pieces in both the festival’s Screening Program and its exhibition in the Garden Hall. He will also take part in a Lounge Talk and a Q&A on the final weekend of the festival, the 7th and 8th March.

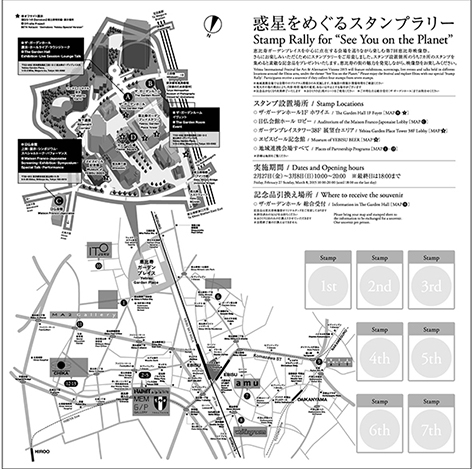

Under the title ‘Our Alternative Past,’ two of Campbell’s films are screening in the auditorium of Maison Franco-Japonaise tomorrow (Tuesday 3rd March), and on the 7th March (followed by a Q&A session).

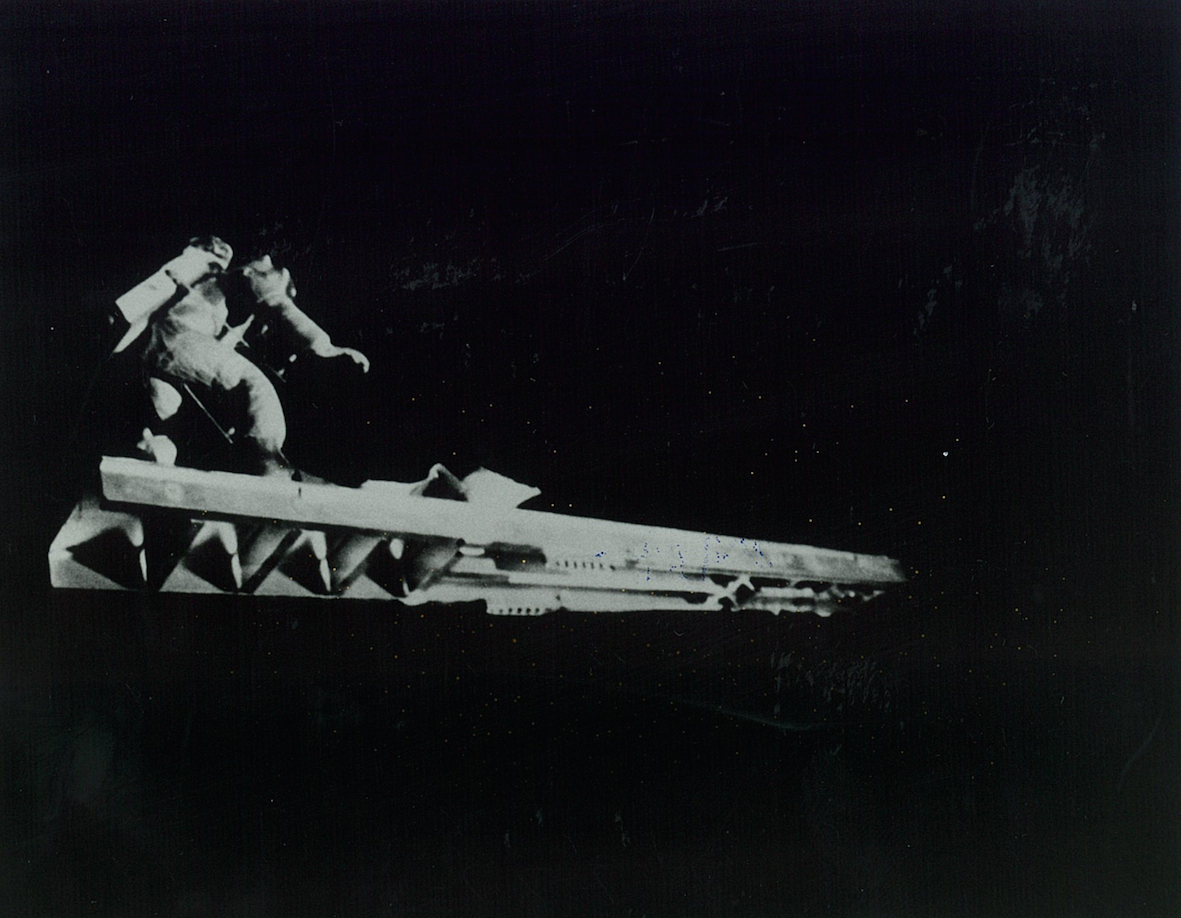

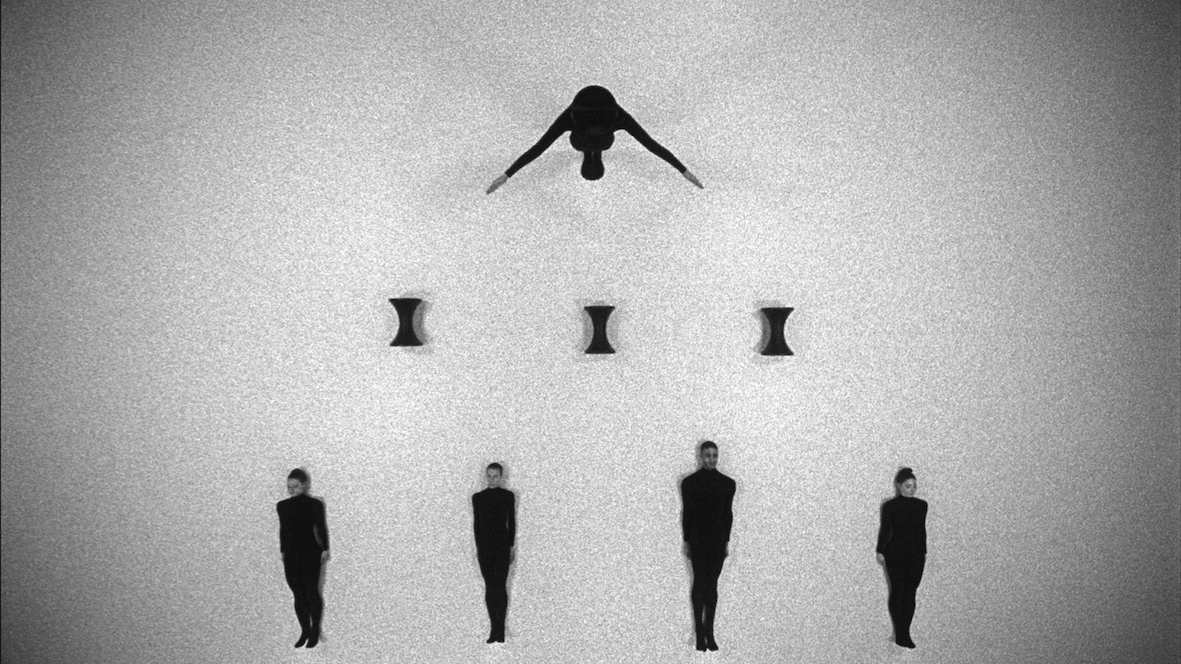

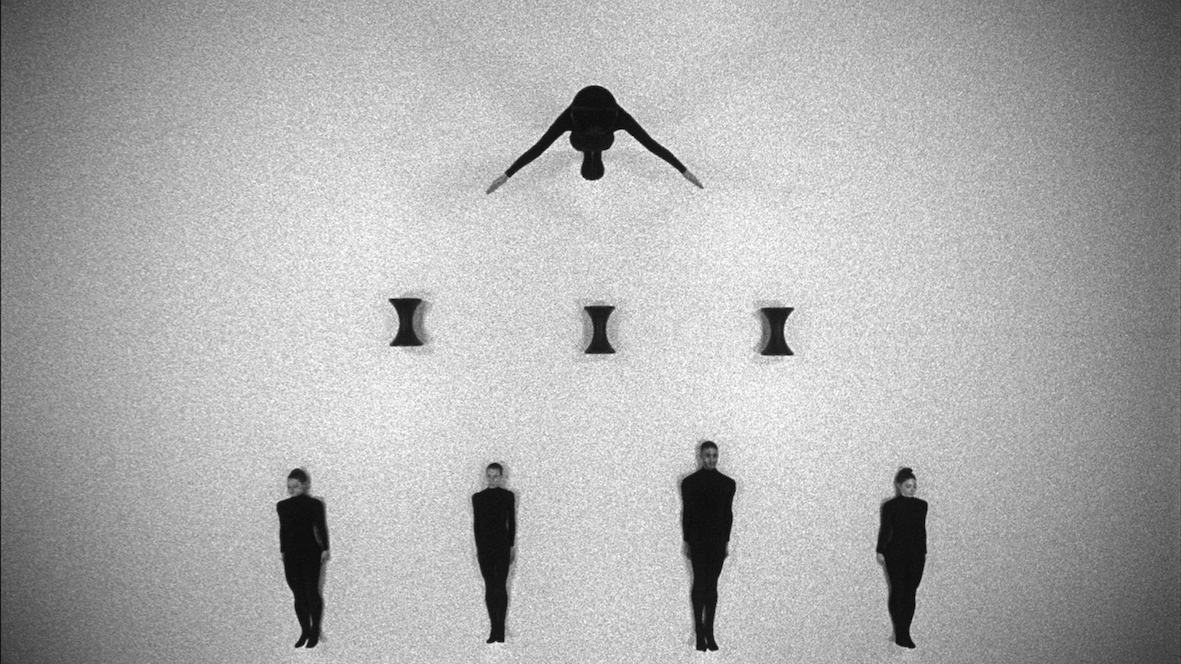

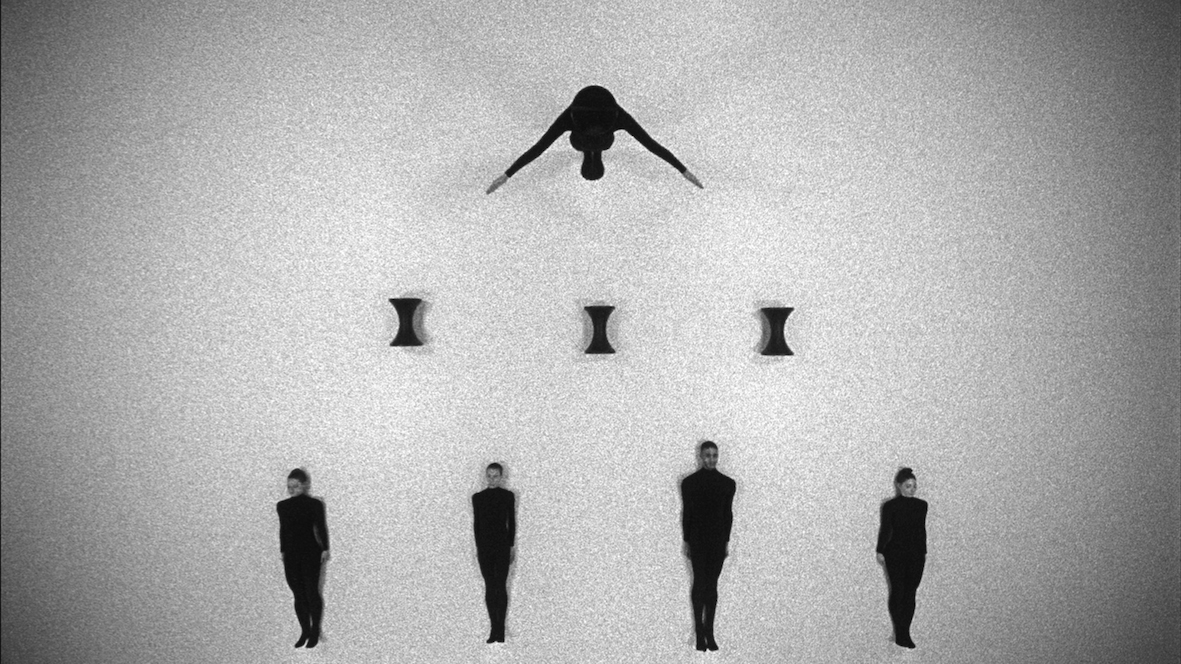

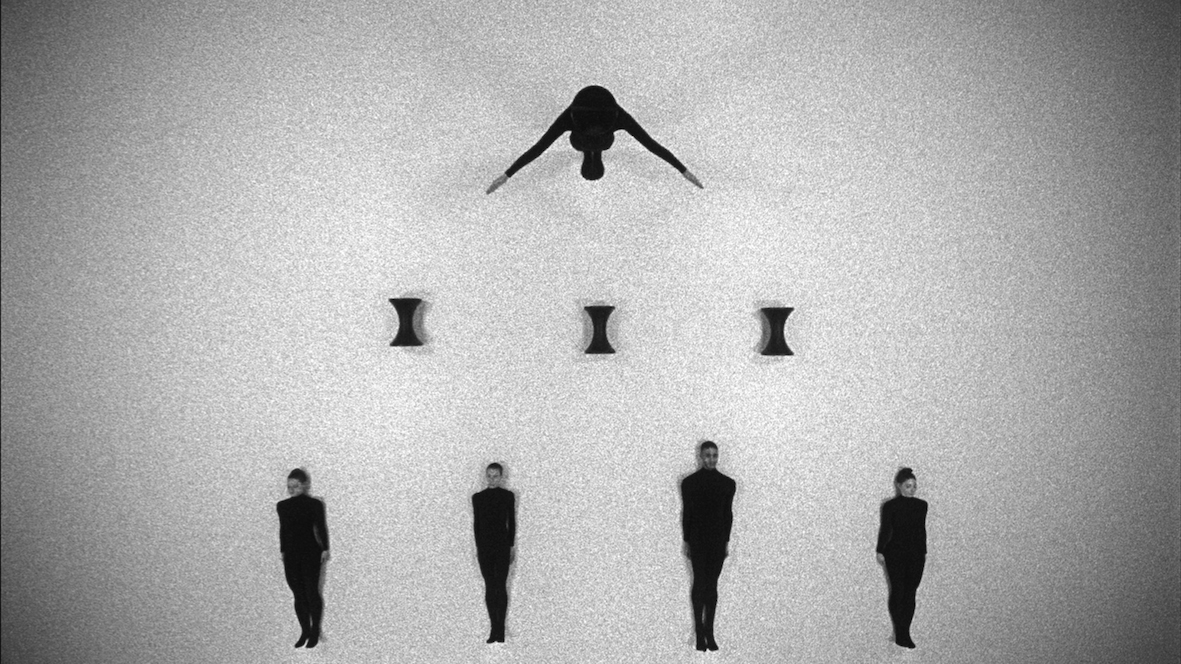

It for Others (2013) premiered in Scotland’s pavilion at the Venice Biennale two years ago, and has intrigued audiences ever since, through its unconventional construction and narrative form. It is almost as if it comprises three separate films. It for Others opens with shots of African artefacts that we later learn are reconstructions of those owned by the British Museum. The voice-over adds an authoritative and studious discourse that soon flows so fast and in such depth that it is hard to keep up. Relating to Alain Resnais and Chris Marker’s 1953 French essay film Statues Also Die, which explores anthropology, collecting and colonialism, this section encourages us to readdress past and continuing struggles of representation, commoditization and power. The film then moves into a sequence of contemporary dance, made in collaboration with Michael Clark and filmed from above so that the dancers (dressed in black, sliding and rolling on a white ground) appear like little diagrams on a sheet of paper. Again the context is political, and this time the dancers’ forms move the discussion into the realm of value and economic theories. Making what appears like equations and sums with their bodies, the projection-screen suddenly looks like a page from an economics book. Finally, commodities themselves are filmed. Bright tubes of toothpaste, sauce bottles, bathroom spray, and a tin of soup are shot against white backgrounds. This contrasts the African artefacts, which were shot in a field of shadows that made them ‘exotic.’ The supermarket objects are today’s artefacts, perhaps. A tin of Campbell’s Tomato soup is placed into the camera’s frame, again and again. Did an African mask give way to Tomato Soup? Do audiences ‘consume’ both in the same way? It for Others raises these questions, but through the relentless pace of its voiceover, leaves us little time to form answers. Perhaps it is exactly in this way that it pushes us to reassess history, authority, and the power of film. Reeling, everything seems questioned.

Duncan CAMPBELL, It for Others , 2013

Courtesy of Duncan Campbell and LUX, London

Bernadette (2008) takes as its subject the Northern Ireland student Bernadette Devlin, who became a Member of Parliament at the age of 21, and campaigned for the rights and representation of her constituency. She employed activist approaches that caused a stir both in Westminster and across global headlines. Deftly montaging archival news reels and interviews that capture Devlin on the streets of Belfast, London and New York, Campbell repaints Devlin’s portrait in an alternative light, highlighting the multiplicities and complexities of her character. She appears coquettish, bullish, vulnerably young, and aged before her years, as the cameras follow her and microphones bob around her head. Several of Campbell’s films explore political and religious troubles in Northern Ireland. The same set of tensions weaves through Make It New John (2009), which is installed inside the Garden Hall.

Duncan CAMPBELL, Bernadette, 2008

Courtesy of Duncan Campbell and LUX, London

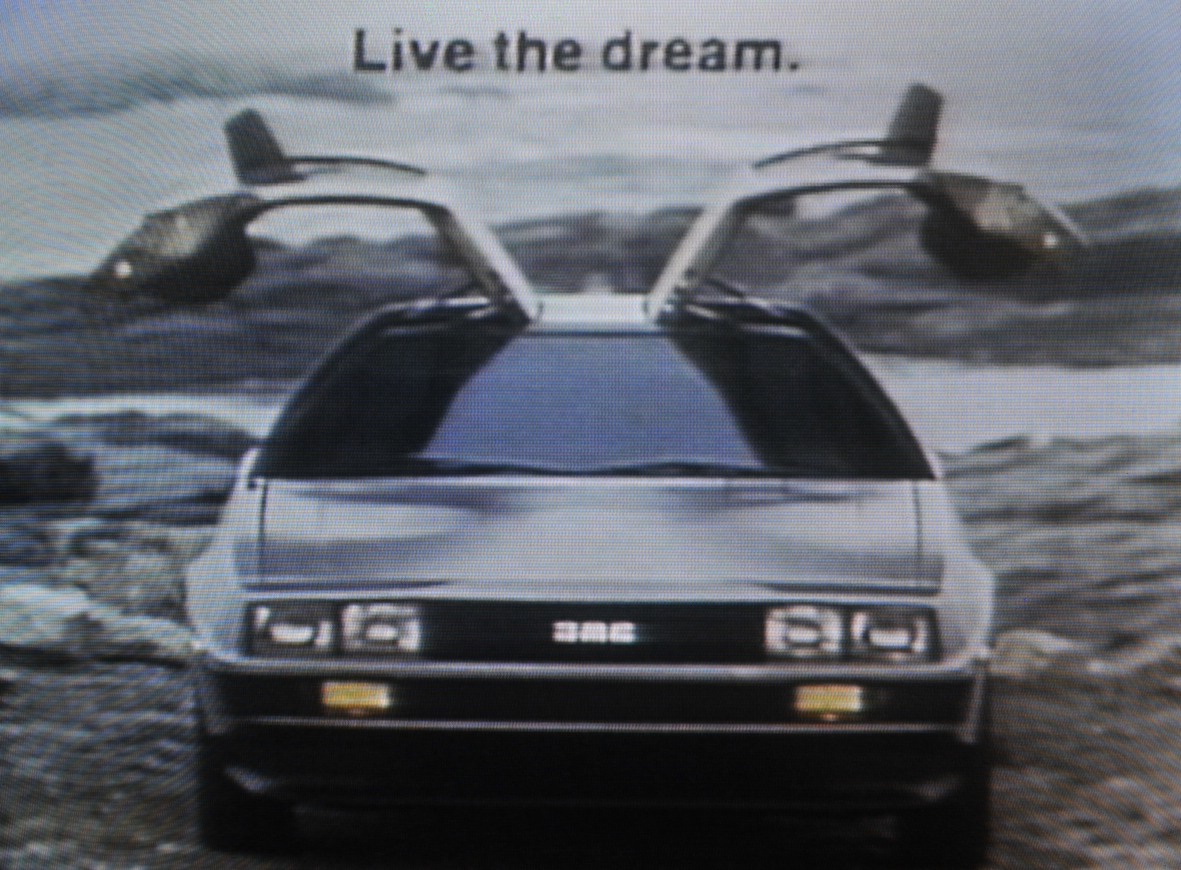

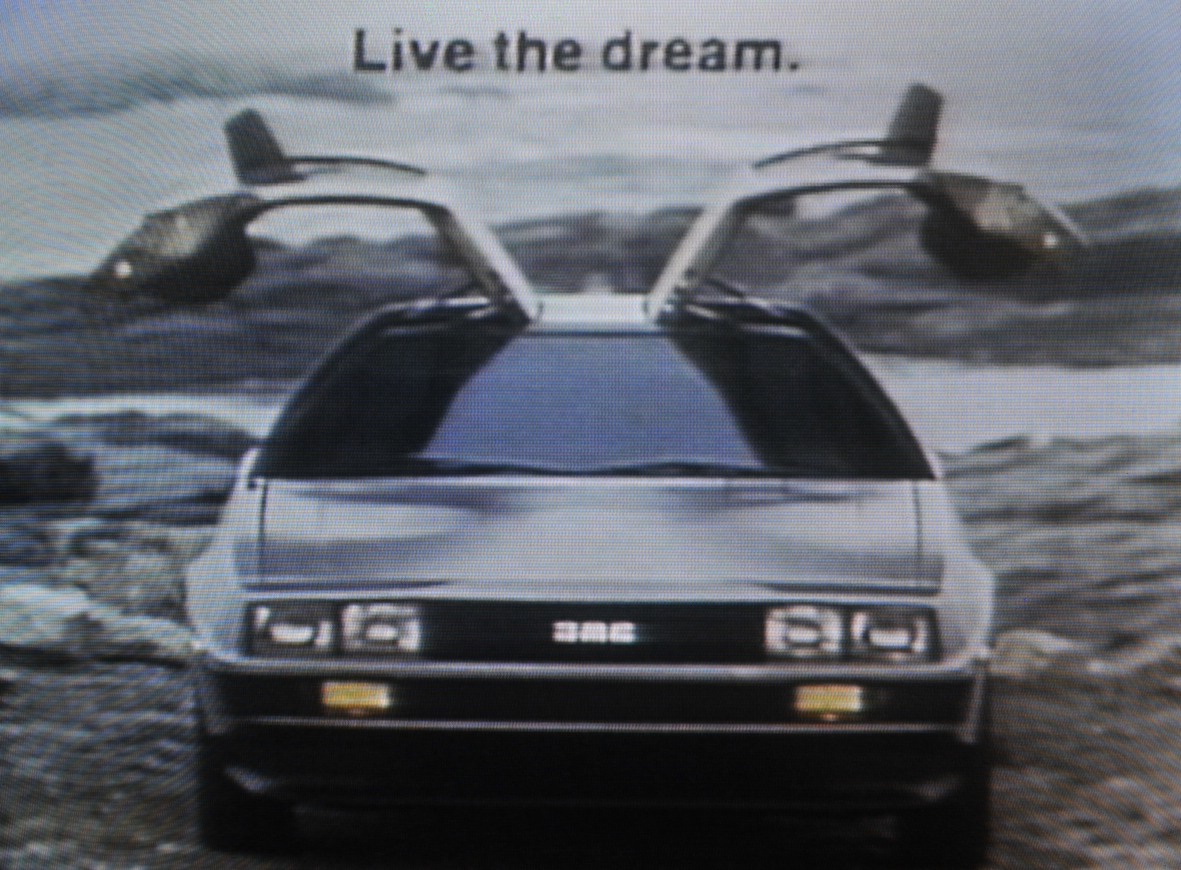

Make It New John will appear strangely familiar to audiences who know the cult films Back to the Future. These films featured the DeLorean car as an epitome of futuristic transport and technology. Campbell focuses on the real life of this iconic car, and specifically, the factory in Northern Ireland that was set up to manufacture them, but that closed within a year of opening. Not a single shot from Back to the Future appears in Campbell’s film, and through this very absence, the stark contrast between cinematic fantasy and the reality of factory closure, pitiful redundancy packages, and continual political struggles becomes clear. Again, we are offered an alternative look at history. We are encouraged to consider the inconsistency of media as an authority, and how its various forms (TV news, fantasy cinema, art documentary) operate on differing agendas, and each paint their own history.

Duncan CAMPBELL , Make it New John, 2009

Courtesy of Duncan Campbell and LUX, London