Berlin-based video artist Hikaru Suzuki grew up in Fukushima prefecture, and several of his recent works have focused on issues facing the region worst hit by the Tohoku tsunami and earthquake of 2011. Suzuki is one of the four young Japanese artists selected for the festival’s screening ‘See the Light,’ which will take place in the auditorium of Maison Franco-Japonaise this Wednesday (4th March).

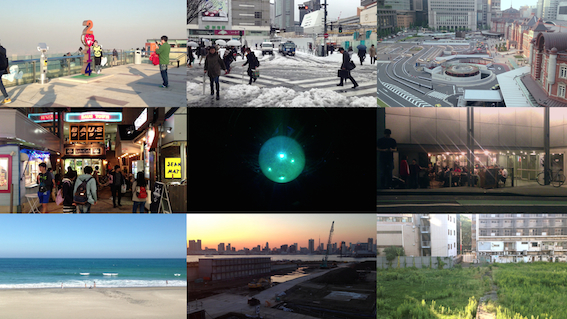

鈴木光《W》2014

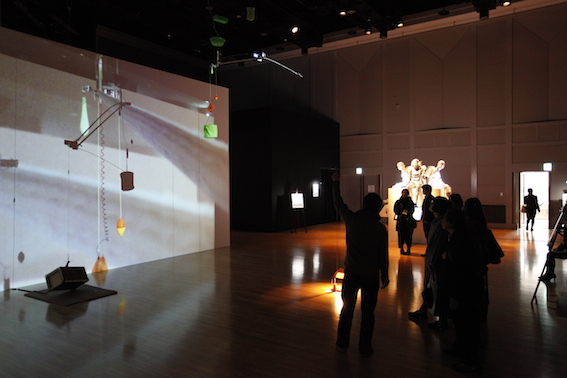

In addition to screening two short films in the ‘See the Light’ program,, Suzuki gave a Lounge Talk earlier in the week, in which he discussed some of the contexts for, and influences on, his practice. Two additional films by Suzuki are on show throughout the festival, on the 4th floor of the Garden Hall. In his talk, Suzuki described his interest in cinema verite, and thinking about this movement – and documentary filmmakers such as Jean Rouch who combine anthropological and more experimental and open-ended approaches – offers a key to understanding Suzuki’s films.

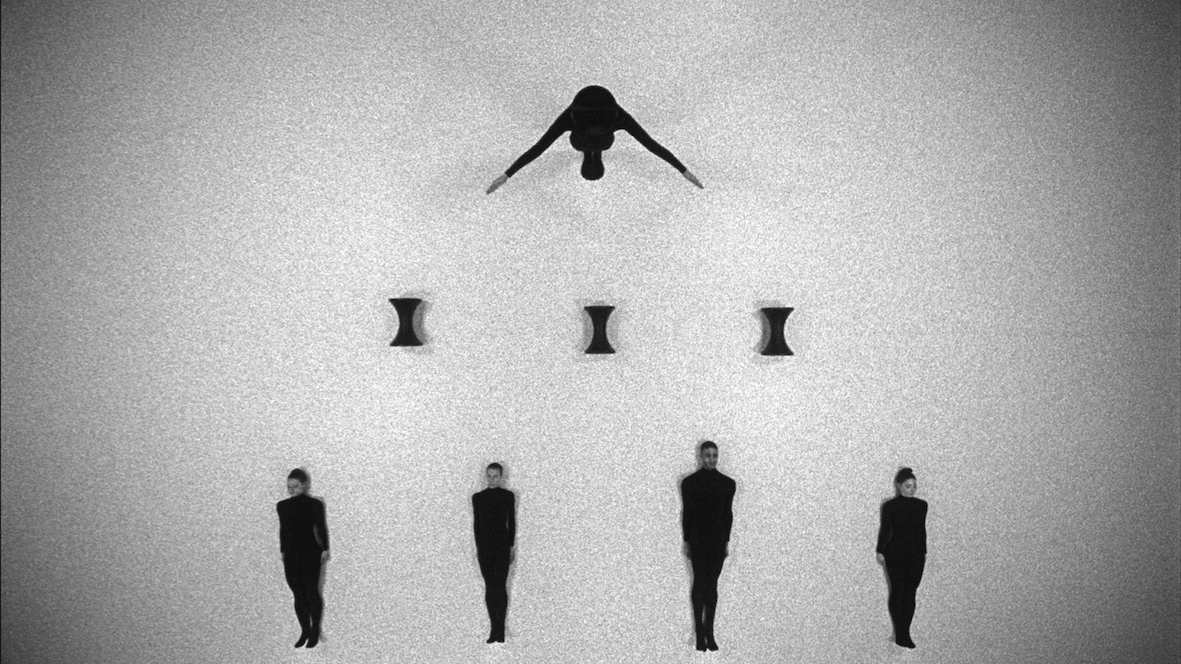

鈴木光《Strahlen》 2014

Every family has secrets and peculiarities, and yet, for those within the family, life can seem perfectly normal. We cannot choose our family, and it can be hard to determine what is ‘normal’ or not from within the bounds of the domestic unit. Such is the case, perhaps, with the family portrayed in Suzuki’s 2011 film Anraku Island. Anraku translates as ‘ease’ or ‘comfort,’ and yet, as the film progresses, a distinct feeling of unease emerges. Perhaps like Freud’s notion of the Uncanny (or Unheimlich), the most homely of family units can house the strangest secrets. In the film, shot with a handheld camera in various locations including a car driving around anonymous streets and industrial parks, Suzuki talks to a young Japanese woman who describes her upbringing in quite a matter of fact manner. Like many children, she grew up in a house with her mother and father. But unlike many families, the parental duo included an additional adult: a Korean immigrant whose identity was unclear, and who took up with the mother – while the father was also still very much present. The mother and father and daughter, and the Korean man (who drank, watched Korean dramas, and had a temper) therefore lived together as a somewhat dysfunctional unit. At one stage, when the mother decided to move to Korea with the Korean man, the father moved with them too. Through a slow pace of narrative disclosure, this unusual story emerges and is not only psychologically intriguing, but encourages us to consider what a ‘family unit’ can mean, and how there is, perhaps, no such thing as a normal family.

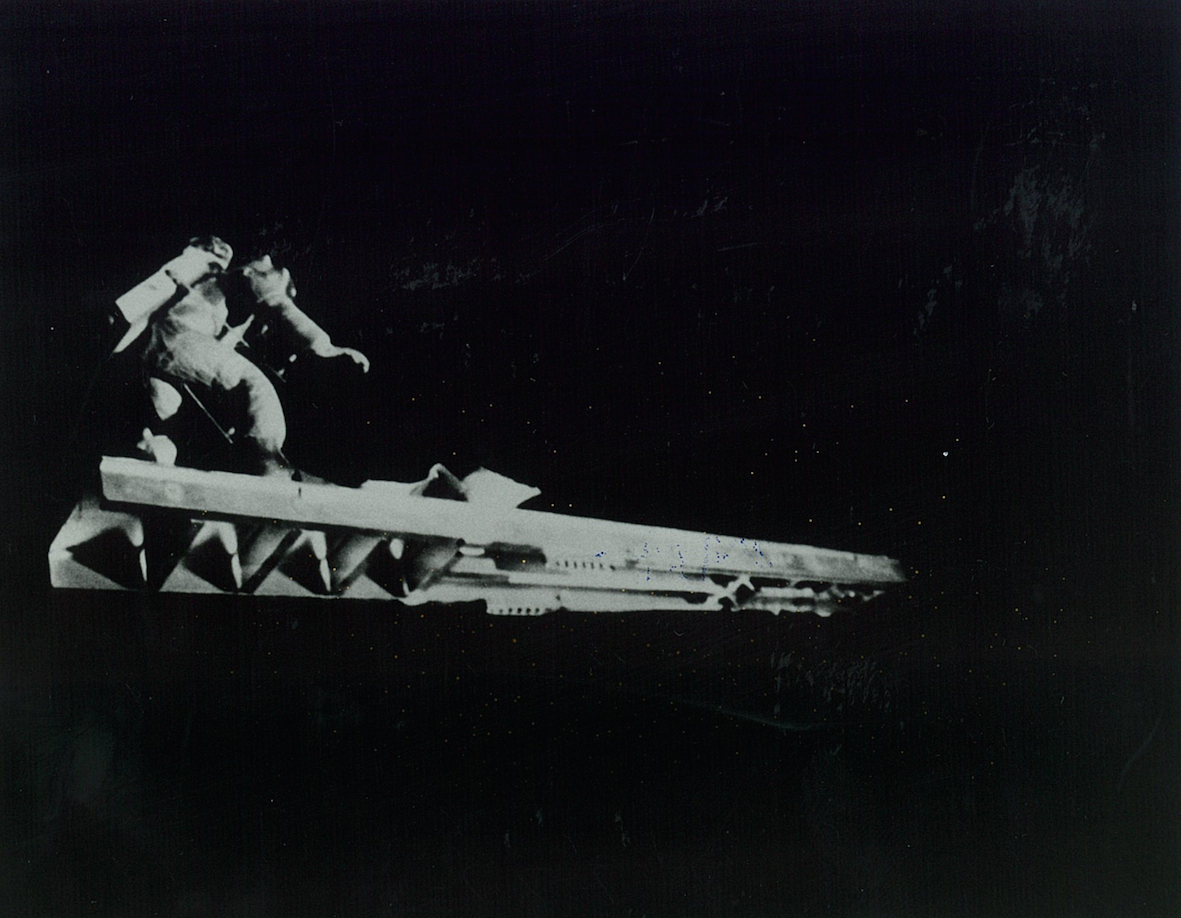

鈴木光《GOD AND FATHER AND ME》2008

This is also the take away from Suzuki’s 2008 autobiographical film God and Father and Me, on display on the 4th floor of the Garden Hall. Through a similarly gradual disclosure of information as exists in Anraku Island, Suzuki points the camera towards his own father. His father is a somewhat elusive and enigmatic ‘healer,’ who has made his fortune curing people who pay to speak to him by phone. Suzuki interviews his mother and sister, both of whom are somewhat estranged from the father, and regard his spirituality – and wealth – with ample suspicion. We also hear from the father’s disciples, who describe his healing powers and the water he blesses and sells. And finally we hear from the father. Does the father believe he is God? Is his venture aimed at fortune alone? What kind of a relationship exists between him and his son, as they sit sharing cigarettes and Suzuki films his father’s phone calls…? Question after question emerges in the film’s strangely oppressive atmosphere. And, as with Anraku Island, we are gradually drawn into the narrative, the family, and film’s potential to capture and complicate reality.